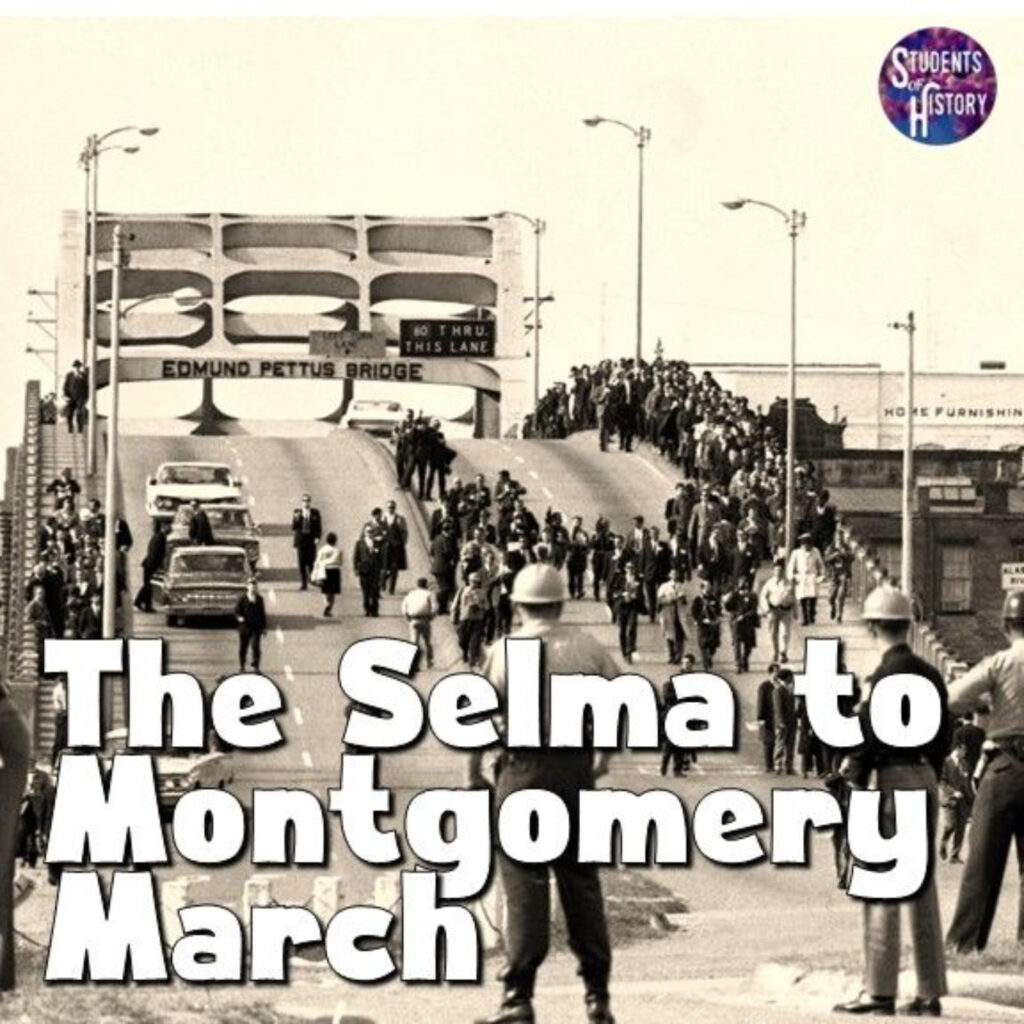

Two weeks ago, I had the opportunity to walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma Alabama.

I also had the opportunity to retrace, albeit by bus, the 54-mile route of the Selma to Montgomery civil rights march that took place some 60 years ago. Technically the 60th anniversary will be in March 2025.

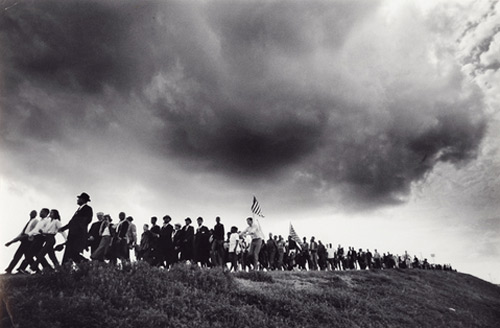

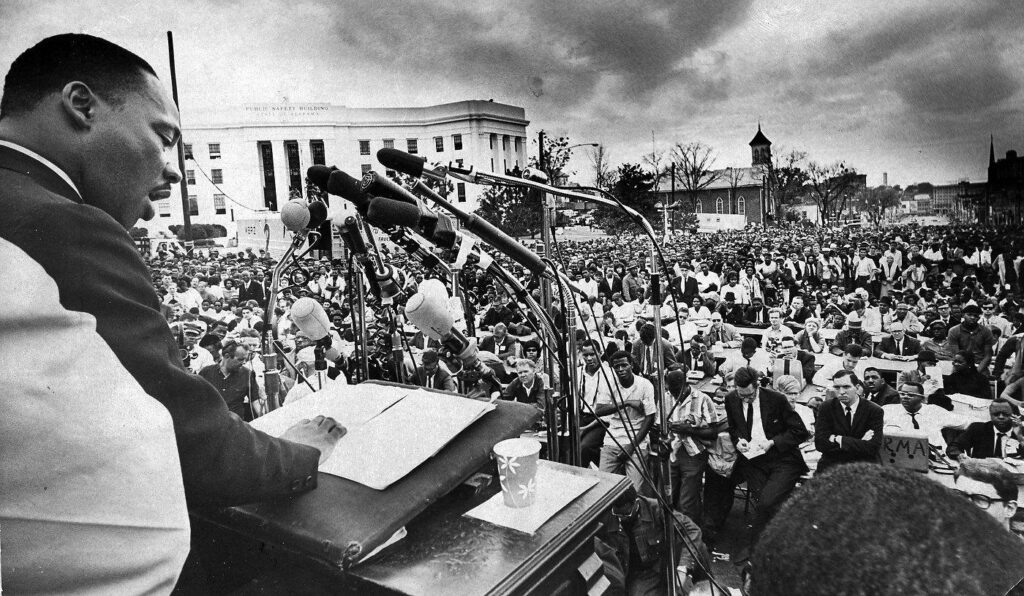

The march that drew international attention was led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and included 299 other brave souls. Although the march was technically limited to 300 people, some 25,000 supporters from all over the country joined them when they finally reached the steps of the State Capitol in Montgomery Alabama.

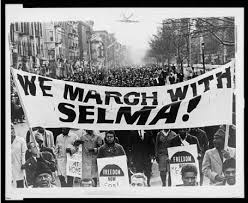

The country, the President and the Congress were mobilized into action because of:

- the public outcry that occurred from the horrific beatings with billy clubs, whips and tear gas suffered by marchers on the Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday, some 15 days earlier (March 7, 1965), and

- the Selma to Montgomery March itself (March 22 1965), and

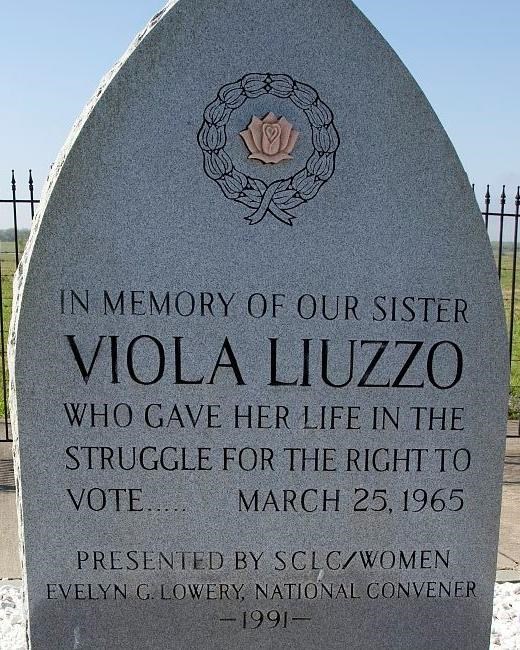

- the brutal cold-blooded killing by the Ku Klux Klan of Viola Liuzzo, a white mother of five from Chicago, who was volunteering to provide needed transportation to marchers (March 25, 1965).

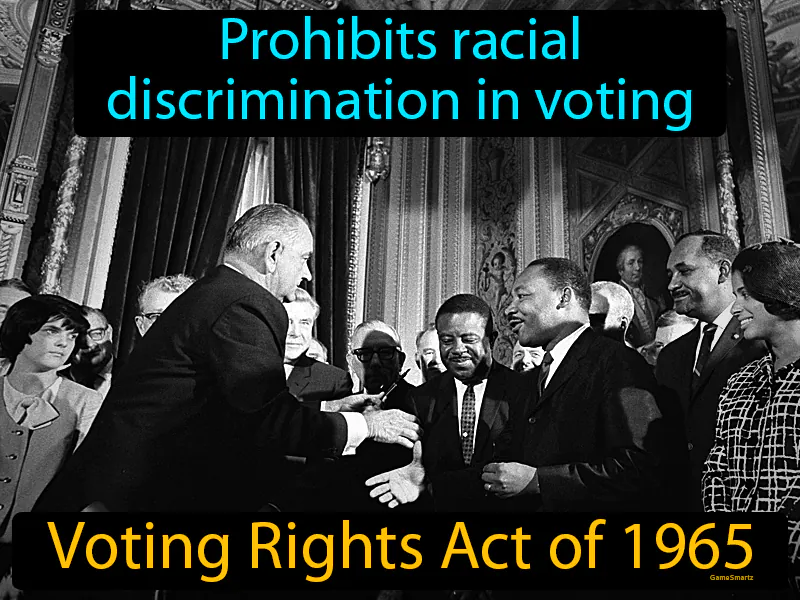

As a result, the US Congress passed with President Lyndon Johnson’s leadership in August of 1965 the Voting Rights Act, which banned literacy tests, interpretation tests, and other discriminatory voter qualification requirements used to disenfranchise Black voters and other minorities.

Before the Voting Rights Act of 1965, only 2% of eligible Black citizens in Dallas County, Alabama, were registered to vote, despite Black individuals comprising about 57% of the county’s population.

The voter registration tests applied to blacks wanting to register to vote in Dallas County were designed to be discriminatory and nearly impossible to pass. Here are some examples of the types of questions or requirements often imposed:

- Complex Constitutional Questions: Applicants were asked to interpret obscure sections of the U.S. or Alabama Constitution, such as explaining the meaning of Article XVII of the Alabama Constitution in legal terms.

- Impossibly Specific Questions: They might be asked questions like:

- “How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?”

- “How many jelly beans in the jar?”

- “How many seeds in a watermelon?”

- “Name every county judge in the state of Alabama.”

- Writing Requirements: Applicants were often asked to write down and interpret a specific passage, such as a complex legal clause, to the satisfaction of the registrar, who had subjective authority to reject responses.

- Arbitrary Literacy Tests: The Alabama Literacy Test in 1965 had 68 questions. Examples include:

- “How many circuit judges serve in Alabama?”

- “Does enumeration affect the income tax levied on citizens in various states?”

- “The Constitution limits the size of the District of Columbia to ____?”

- “What are the qualifications for becoming a member of the Alabama House of Representatives?”

- Endorsements: In some cases, Black applicants were required to have white sponsors to vouch for their character or qualifications, which was another systemic barrier.

Today, the demographics of Dallas County reflect a Black population of approximately 69%. Among registered voters, around 63% are Black, indicating significant progress in voter registration and representation since the 1965 legislation.

Why is it important to remember what happened between March and August 1965, you may ask.

One, it is history. It is true. It happened. We need to acknowledge this history and make sure that all Americans are fully informed on what happened and why.

Our history books and our schools need to make sure that this history is taught to all children.

In addition, it is one thing to read about history, it is another thing to see, feel and in some way experience history. My hope would be that every history teacher in America today would find a way to bring their class of students to Selma and Montgomery so that they could get a chance to more fully understand and experience what happened and why.

The second reason that I believe that it is important to remember the events some 60 years ago is that maybe, just maybe, we can learn from history something that will be helpful to us as a nation right now.

Specifically, I am referring to the seemingly deep divisions that we have in our country today. We can’t even find a way to talk with each other, the divisiveness is so deep. Whether it be about immigration, the economy, democracy, wokeness, Ukraine, Israel and Gaza, transgender, homelessness, public safety, ad infinitum.

The divisions that separate us today pale in comparison to the divisions that separated blacks from whites in Alabama and several other mostly southern states in the 1950’s, the 1960’s and before.

Somehow, over time, we have been able to break down the barriers that separated blacks from whites, to make it possible for each individual regardless of their color to have the same opportunity to exercise their constitutional and human rights, and to bring about a coming together of the races. As I say this, I realize that there is still a ways to go to bring our different races and cultures together. However, there is no doubt that significant progress has been made.

The question I find myself asking myself is — are there some lessons from the civil rights movement that might be useful in tackling the divisions that we have in our country today?

I would like to suggest that yes, there are some lessons that would be helpful.

- One, remembering that it is important to stand up and be counted when there is an injustice and when false information is being distributed.

- Two, organizing at the local level around those injustices and misinformation can have an impact – in Selma and in other communities that make up the great diversity in our country.

- Three, being willing to peacefully, non-violently demonstrate as a way of making sure that every American is fully aware of the issue at stake and every American has the opportunity to participate in finding a resolution to the issue at hand.

- Four, remembering that the civil rights movement did not get resolved in a few months, or a few years. It has taken decades, and it is still on going.

Or, to put it another way, why are we looking for the President and the Congress to resolve the issues that we appear to have deep divisions of opinion on today?

Why don’t we deal with these issues ourselves at the local level? Why don’t we – at the local level, not the state or national level — bring people together who have widely divergent views on an issue that needs to find resolution, a common ground. An example would be immigration or homelessness.

Bottom line. I know this idea of taking a lesson from the Civil Rights Movement may seem pollyannish, but…

I came away from my immersion in Selma and Montgomery this past week invigorated and hopeful…

- In the potential to resolve our seemingly intractable divisions in the country today.

- In the potential for our citizens to get together at the local level – in neighborhoods, in communities, in towns, in counties.

- In the potential for these local efforts to significantly impact the national debate and actions.

great job, Neil

This was an excellent and powerful blog Neil. What an emotional experience that must have been to stand on that ground where such brave people took a stand against seemingly insurmountable hatred and obstacles.

This was such a necessary blog, especially now! knowing our nations’s past is so important and seeing it first hand is amazing! I have always said that local politics is where things get better! thanks for sharing such an important experience!

I couldn’t agree with you more Neil…baby steps!

Great blog Neil. I did a similar visit two years ago with my friend and colleague Frank Martin who ran the Birmingham transit system, in Birmingham visited the 16th Street Baptist Church, the park across from the Church where Bill Connor’s dogs attacked the kids from the Children’s Crusade, and the National Peace and Justice Memorial (the Lynching Memorial) in Montgomery. All unforgettable.. All sacred places in our history.

lee,

yes, indeed. stay tuned for my blog tomorrow about the Lynching Memorial.

neil